Hili Perlson on Bettina Pousttchi's exhibition Horizons at Buchmann Galerie in the January Edition of Artforum Magazine.

Reviews – Bettina Pousttchi

Hili Perlson

in: Artforum Magazine January 2026

Bettina Pousttchi’s “Horizons” offered a reading of Berlin’s built environment as a palimpsest of absence and return, one into which she has delicately inserted her own scripture. The show extended from her seminal project Echo, 2009–10, in which she covered the facade of the Temporäre Kunsthalle with 970 posters re-creating the shimmering front of the controversially demolished Palast der Republik. The privately funded Kunsthalle operated from 2008 to 2010 on Berlin’s history-laden Schlossplatz, overlooking the recently razed Palast, an asbestos-contaminated yet beloved German Democratic Republic landmark. The Kunsthalle held within its provisional structure not just exhibitions that spoke of Berlin’s singular spirit in the early years of the new millennium but also a not-so-far-fetched vision of what could be if only the city would invest in its thriving contemporary art scene. Instead, Berliners got the Humboldt Forum, an overpriced replica of the seventeenth-century Baroque palace that once stood on the spot. Pousttchi’s six-month resurrection of the socialist architecture that had been erected in its stead—a mechanical reproduction on a building-as-proposal—was both image and ruin, a distilled rebuke of decades of bad policy.

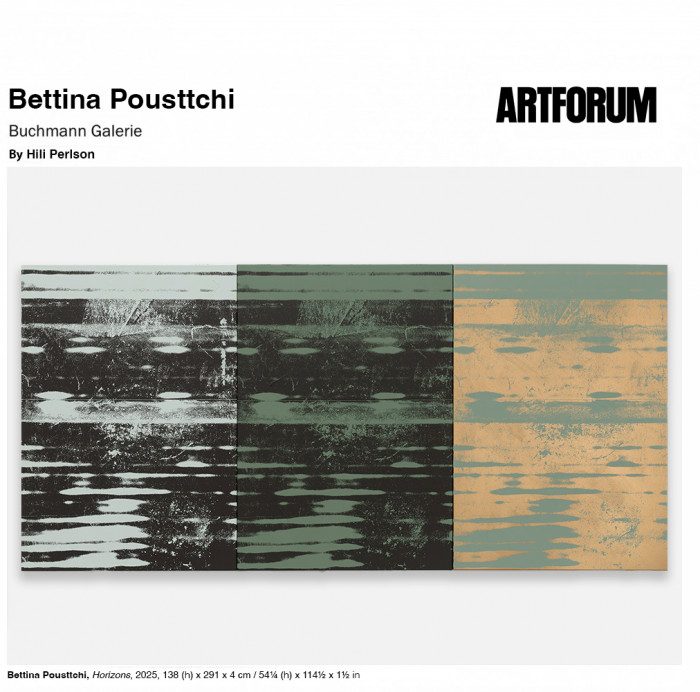

Fast-forward fifteen years: Pousttchi photographed fragments of the weathered Echo prints she had kept in her studio, then silk-screened them onto monochrome canvases with acrylic paint. Materially speaking, the resulting works, each titled Horizons (all works 2025), would be considered paintings. But Pousttchi still regards them as photographs—new embodiments of her two-decade exploration of what a photographic image can become when conceived of as a container of touch and time. Installed in the gallery in pairs or as triptychs, the canvases generate a subtle sense of flow, suggesting continuation rather than repetition, although each arrangement bears the same fragmented motif. The canvases’ colors—red, green, ocher, gold, white, or simply unprimed—evoke the changing reflections of the skies, the River Spree, and occasionally the sun on the reflective-glass cladding of the erstwhile Palast, which was best experienced when biking down the storied boulevard Unter den Linden.

Meanwhile, ceramic sculptures, each titled Earthwork, translate this meditation on a city damned to perpetual transformation into seductive material manifestations. Pousttchi approaches ceramics through architecture, not craft, recalling clay as one of the earliest building materials and the foundation of Berlin’s nineteenth-century industrial boom. This industrialization came about thanks to the invention of the Hoffmann kiln, which allowed continuous brick production for the first time and revolutionized the brickmaking industry in and around Berlin. Using molds in architectural-preservation archives, she has reoriented historic clinker-brick forms that blend ornamentation and function—extruded, round-edged, neo-Gothic—glazing them in saturated hues. Most of the Earthwork sculptures are two-part pieces and were exhibited on a single plinth, staged tilted slightly inward toward each other, along the gallery’s perimeter. One shape that repeats in several multicolored pairs recalls a blunted arrow facing down, as if it were stuck in limbo between structure and adornment. Another brick design appears only in one arrangement, containing six pieces in three similarly glazed pairs, lilac flanked by navy blue. With its one-sided curve, this form—glossy and alienated from its use—feels more space-age than Belle Epoque, an era that defined much of what Berlin still felt like well into the early 2000s.

Two new metal sculptures from Pousttchi’s “Vertical Highways” series, both 2025, shot upward from two spots across the gallery. Pousttchi makes these works from steel guardrails, urban instruments of safety and control, twisted and bent and positioned upright. One, powder-coated black and white, placed near the entrance, is about six feet, nine inches high, at once anthropomorphic and totemic. The other sculpture is bright red, an eleven-foot piece that recalls her monumental public-art piece installed outside Berlin’s central station. With all of the work in the show, the cityscape in its various incarnations is ever-present, as is the artist’s inscription in public space. Together, the black, white, and red palette carries an uneasy double resonance—socialism and fascism, attraction and repulsion—invoking Germany’s turbulent history. With much conjecture recently about Berlin being “over,” the show was a good reminder that nothing has ever defined Berlin more accurately than forever painfully wading through the process of becoming.

The article in Artforum Magazine can be found via this link.